A Very Special Moment in Summit County

On Tuesday, August 25th, a report came in on Ohio Chase Birds about a Brown Booby at Nimisila Reservoir in Summit County, Ohio. The bird was found by Henry Trimpe and hundreds of birders have since gone to see this bird over the past few days. Chris Collins, of the Rogue Birders and OOS Board Member, was curious about Henry’s story of finding the bird so he reached out to Henry to see if he would be willing to share his story here. Reprinted here from the Rogue Birders blog. Enjoy!

A Very Special Moment in Summit County

by Henry Trimpe

Arguably my favorite part of being a birder is that every time you walk outside your door, you never know what you will find. Often times, you can put yourself in a good position to find certain birds by knowing where to look, when to look, and most importantly, what to look for. However, there is also at least some element of chance to every birding adventure. For many of us, just that chance of seeing something new, something uncommon, or even something that doesn’t belong within a thousand miles is what excites us every time we pick up our binoculars.

On Tuesday August 25th, I was thrilled to be heading down to Nimisila Reservoir to watch the evening congregation of 30,000+ Purple Martins. Despite the fact that the Martins have used Nimisila as a staging ground for years on their way south, I had never witnessed the spectacle. I fully expected to be blown away by the mass gathering of Martins, but had no idea that what seemed like an innocent late summer evening would turn into one of the most memorable birding days of my life.

As soon as we arrived near the water in parking lot C6 at Nimisila, the first birds we saw were a pair of Ospreys on a nearby snag. At 7 PM, there was not yet a single Purple Martin in sight. As many reading this would, the only logical action was to scan the lake to see what I could find.

The very first bird I got my binoculars on in flight immediately struck me as out of the ordinary. It appeared dark in color, but I was looking almost directly into the sun and the lighting was far from ideal. At first glance, going by only size and shape alone, my first thought was Caspian Tern. After watching the bird for about 20-30 seconds, it moved to better light and I realized that this was an overall brown bird – definitely not a Caspian or any other local Tern. Next, it barreled toward the water on an angled dive. The bird surfaced, and at that point I lost it in the sun and could not relocate. I vividly remember then saying to my fiancé Sarah “there is something out there that doesn’t belong here”.

Is it a tern? Or something completely unexpected?

It took about 15 minutes to relocate the bird. At that point we were joined by Dwight and Ann Chasar, as well as my dad, Jim. After relocating, we got much better views of the bird in flight, on the water, and perched on its favorite snag. As someone who follows national rare bird alerts, I was very aware of Brown Boobies being found in Arkansas, Missouri, and other far-from-home locations as a result of recent storms. We had a hunch, and after photographing and studying the bird for some time we came to a conclusion. All the while, massive numbers of Purple Martins were flocking together in every direction. After looping around in flight many times, the Booby flew out of sight with dusk approaching. We shifted our focus to the Martins – an amazing spectacle that I would recommend to anyone. When we got back to the car, I posted the sighting in the Ohio Chase Birds group, and the madness then ensued. I knew we had found an amazing bird, but had no clue at the time that this was a first state record.

Finding a tropical seabird in a Midwestern lake is not an everyday occurrence, so there was certainly a major element of “right place, right time” that allowed me to find Ohio’s first Brown Booby. However for me, there is much more to the story than that. As early as I can remember, I was intently watching and identifying every bird in my backyard. Before age 10, I was a regular on the local spring bird walks under the Station Road Bridge in Brecksville. By the time I graduated high school, I had an extensive knowledge of all North American birdlife, mostly due to my passion for reading and learning everything I possibly could. It was the countless hours of studying field guides that allowed me to be prepared to ID a bird whose regular range barely comes in contact with any part of the United States. If this article inspires anyone in any way, I hope the message is that the more we study and learn about birds, the more we will be able to identify them, enjoy them, and protect them. This holds true whether we are talking about a Brown Booby that showed up where it had no business being, or the Chimney Swifts circling above your front yard.

For me personally, possibly the best part of all of this has been the fact that the bird has been so cooperative, and has stayed around for the better part of a week. I have been glued to eBird and Facebook over the past four days and have been in awe at the number of birders who have come to Nimisila to see the Booby. Ohio has so many amazing birders (many of whom I don’t know at all personally), and I am glad that so many people have been able to get a new state bird, and in probably the majority of cases, a new life bird. As I am writing this on Saturday, eBird reports are still pouring in, with birders traveling all the way to Summit County from multiple other Midwestern states. Those who have seen the Booby thus far are birders of many different experience levels, with many different motivations. Some are most interested in adding a new tally to their list. Some are most interested in getting the best possible photo. Some are interested in studying a species that they very reasonably may never see again. All have been brought to the same place by one single bird, and to me that is an incredible thing.

Thousands of Purple Martins staging at Nimisila Reservoir

I have seen a great deal of discussion surrounding the Booby’s chances of survival with colder weather eventually approaching. If the bird does not find its way back south, there is certainly a good chance it will not make it, as we often see with these types of vagrants. This is not the first seabird to be blown off course by a hurricane and definitely will not be the last. While we all hope the ending will be positive for the bird, it has given us all a chance to admire the sheer unpredictability of nature in a unique way, close to home.

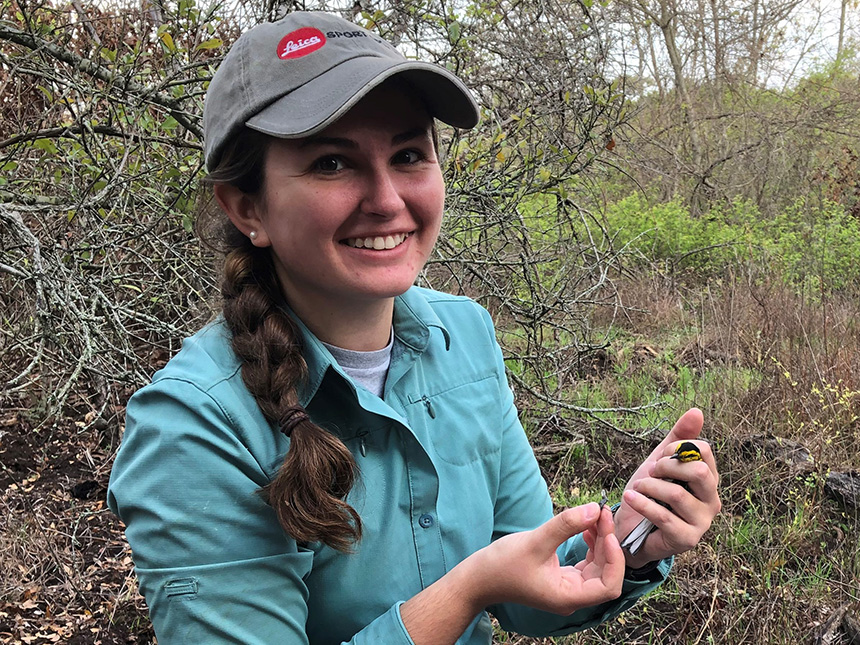

I was honored to have spent this memorable evening with a few very important people to my birding journey. Dwight and Ann Chasar have been teaching me about birds and birding in the Cuyahoga Valley National Park for nearly 20 years – since I first started going on bird walks as a kid. It was a complete coincidence that they showed up at Nimisila to watch the Martins on the same evening as I did. They undoubtedly played a huge role in helping to identify this bird. Knowing how much time they have dedicated to birding in Summit County over the years, I am so glad they were able to be a part of this moment. Summit County as a whole has an awesome birding community, and I’m very happy that this bird decided to pick Nimisila over any of the countless other bodies of water across the state. Had it picked somewhere else, I would have been right there among the masses parading to see it. My dad, Jim, was also present as he has been for the vast majority of birding experiences in my life. He can be credited for fueling my passion for birds from a young age. Finally and most importantly, my fiancé Sarah got to witness this as one of her very first birding moments (and in the meantime snapped some pretty darn good pictures of the bird in the water, before we even had the ID confirmed).

When it comes to vagrants, I always wonder how many others are out there that have not been found. In this case, with the number of birders coming to Nimisila each evening, I am confident someone else would have found it later in the week had we not on Tuesday. But at some other lake, or in some other backyard, there are certainly many more oddities that are never detected. Fall migration is upon us here in Ohio, and there are many birds out there to be found. Best of luck to all in this wonderful season, and thanks to everyone who has reached out in the past couple of days!